I came across Alice recently and love it. It isn’t only what the product claims to do, it’s how their business model aligns so well with their users and customers.

(FYI – I’m not involved with this company in any way. I don’t know the team or invested…although I wish I was an early investor!)

First, what it does.

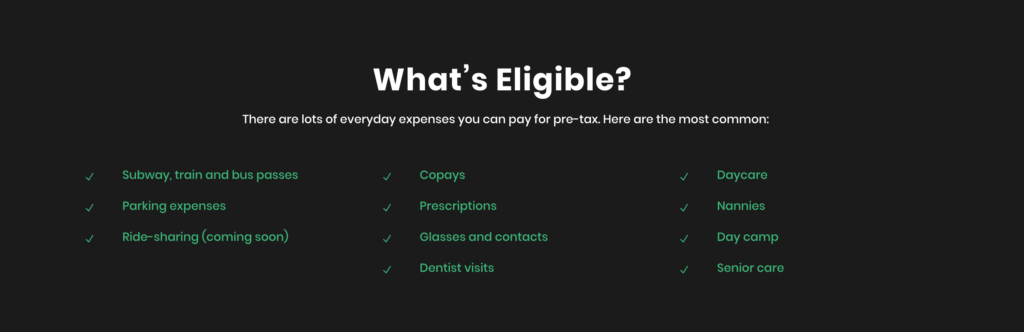

It’s an app that employees connect to their credit cards which monitors their spending. When it identifies charges eligible to be reimbursed with pre-tax w2 dollars, Alice submits the deduction to the employer’s payroll system automatically.

This is ingenious because it requires no behavior change from anybody and makes money for everybody at the same time, including Alice.

- Employees – It’s simple to connect an app to your credit card and you’re more than happy to find out that bus pass you bought is now being paid for with pre-tax dollars. That’s money in your pocket.

- Employers – It wires into the payroll system to automatically submit deductions. Simple. Every dollar deducted pre-tax reduces the employer’s payroll tax burden (Medicare, Social Security, etc…). That’s keeps more money in company’s bank account.

- Alice – This is where incentive alignment comes in. They save the employer money and the employer pays Alice back a portion of the savings. That’s money in Alice’s bank.

The last part may seem obvious, Alice takes a cut of the savings. But consider how powerful that is when compared to a service that negotiates on a patient’s behalf to lower their medical bill. The patient received a $10k medical bill. The company negotiates it to $2k and charges the customer 5% of what they saved them, $400.

Sounds great in theory, unfortunately the patient didn’t have the $10k to start with and probably doesn’t have the $400 to pay the service provider. Even if they are relieved the bill amount was reduced, the business model isn’t fully aligned with the customer.

In Alice’s case, the employer does have the money and is happy to pay a percentage to Alice. They were going to spend it anyway! And now they get to pay less.

It’s interesting to think why this product has emerged now. What makes it possible today versus 5 years ago? A combination of things:

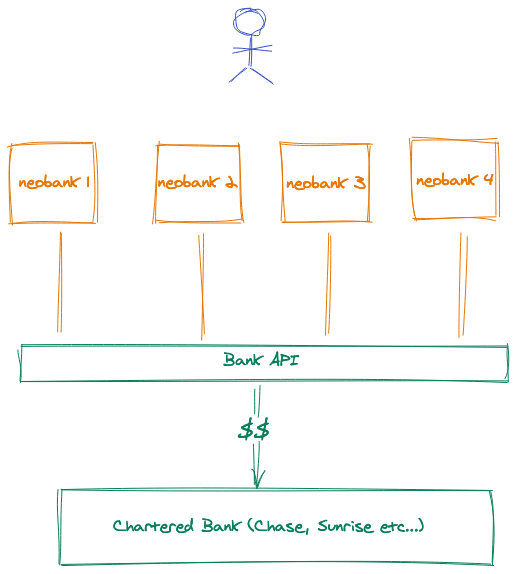

- Fintech Infrastructure – APIs to monitoring card transactions (thanks Plaid!) have made this 10x easier.

- API Economy – Of course, the payroll providers all have an API. Try having done this even 5 years ago. Remove the benefit of auto-submitting the deduction and now you have to ask the employer to do work or change their processes. Much harder sell.

- Consumer Habits – That fintech infra has made services that tap into your financial accounts so much more prevalent, resulting in more apps that do so. People have gotten used to it and are more willing to try.